2016 Competition

Boston 2024

2016 Competition Overview

The 2016 Lyceum Competition was inspired by the proposal that Boston be the host city for the 2024 Summer Olympic Games. And while we know with certainty that the Olympics will not be hosted in Boston, the foundation of the design problem remains exciting and challenging even as a theoretical exercise. Therefore, the 2016 Lyceum program asks its student competitors to approach this design problem using Boston as the hypothetical host city. The Lyceum founders are especially excited to see the ideas and concepts in response to this program because Boston is the Lyceum’s home.

Using the Boston 2024 Olympic bid as a scenario, the Lyceum Fellowship competition will explore urban, architectural and landscape issues in a six week design studio.

Boston’s successful bid for the US city to host the 2024 Olympics, has been met with a mix of concern and guarded optimism. Proponents have touted the marketing boost that the Olympics would bring to the city, while detractors point to the financial track records of host cities, the disruption caused by the Olympics and the ruins of athletic facilities abandoned after the Olympics are over. The debate prompted by the prospect of hosting The Games has been a productive dialog about the city, its infrastructure, it long term vision, and its values.

During the selection process the host city necessarily markets itself to attract The Games. In Boston’s case, the Boston 2024 Olympic Committee showcased Boston’s history, its universities, its innovation economy, its transit, and its walkability. Literature supporting the bid claimed that Boston’s Olympics would be sustainable, walkable and compact. It would also be fiscally responsible, with a plan to utilize many existing sports facilities and plans to recycle structures that would only be used for the duration of the games.

Boston as a city and a venue has been on display. It is at once an asset, a showcase, and a photogenic backdrop to a media spectacle that inevitably transforms host cities in significant ways. Highlighting Boston’s urban qualities as assets and pointing out the limits of existing infrastructure, like Boston’s ailing transit system, has been productive in shifting the discussion towards Boston’s long term plans, regardless of whether Boston is eventually selected.

In planning for London 2012, urban economist Ricky Burdett noted that the Olympics would serve as a great catalyst for constructing housing and rail infrastructure that London needed to build anyways. Critics have argued that the Olympics would divert attention and funds away from much needed investments and would ultimately result in wasted resources and underutilized sports venues. Images of former Olympic facilities abandoned and overgrown epitomize the wastefulness of “single serving” Olympic architecture. In Athens, the stadia built for the 2004 Olympics are modern day ruins in just 10 years after the events.

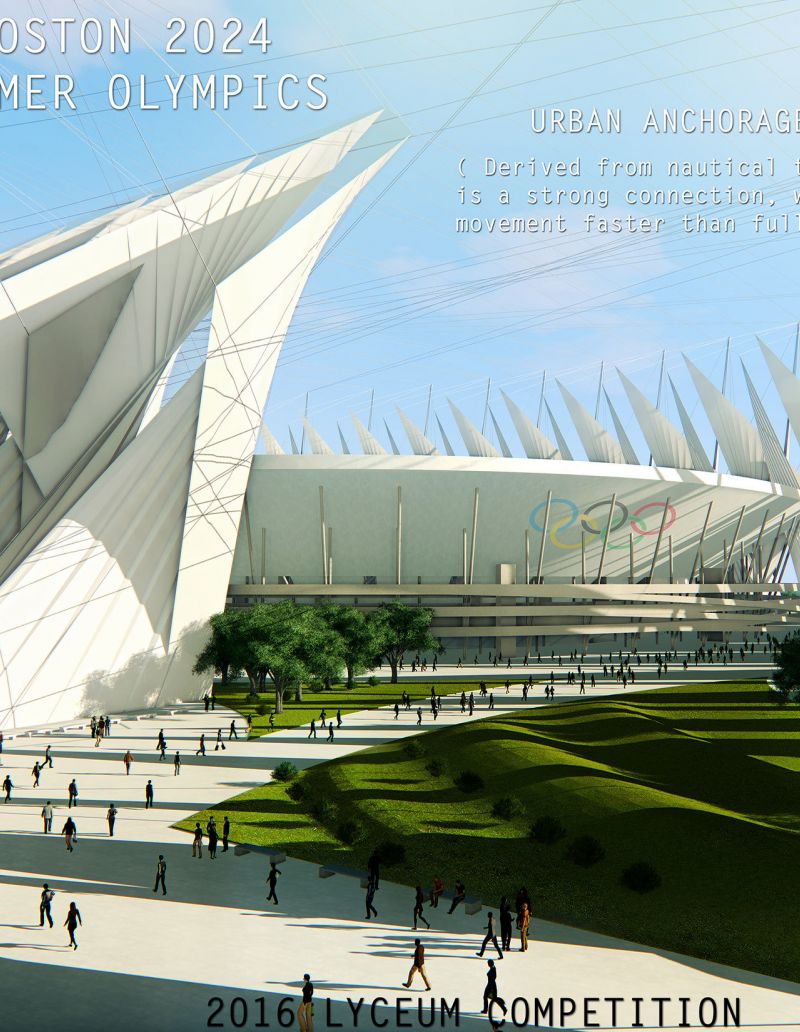

While the urban is the subject of the Olympic bidding process, the Olympic events are ultimately hosted in architectural structures, often purpose built, and often over scaled for daily use. Iconic stadiums built for the Olympics include Frei Otto’s Munich’s Olympic stadium integrated into the park, and Beijing’s memorable “birds nest” stadium by Herzog and deMeuron, and the “Watercube” by PTW. The recent controversy over Zaha Hadid’s proposed Tokyo stadium attests to the fact that Olympic architecture remains a contentious issue. Too big, too expensive, too useless, are claims brought against contemporary Olympic structures. They are short term spectacles with little to contribute to the city in the long term.

What then, can be learned from the Olympics in the context of an architecture or urban design studio? Clearly there are urban design and transportation planning issues around the design, location and conceptualization of the Olympic venues. Architecturally speaking, the Olympic facilities provide a rich array of structures for hosting sporting events, as well as athlete housing and media services. More importantly, however is the pedagogical benefit of stimulating the debate around the Olympics as an agent for affecting change in the built environment.

The Boston2024 bid documents propose to accommodate many events in existing facilities like the Boston Convention and Exhibition Center, Gillette Stadium, the TD Garden, and Harvard’s athletic facilities. Purpose built structures would include a new Olympic stadium to seat 60,000 spectators, to be built on a teardrop shaped rail yard between highway I-93 and South Boston. The proposed stadium development area has been aspirationally called “Midtown,” despite the fact that its current context is a placeless zone of primarily underutilized industrial sites and uses. The current plan seeks to link the Olympic venue with the Fort Point Channel waterfront and the Rose Kennedy Greenway. Athletes’ housing is currently planned for the Columbia Point/ U Mass Boston sites to the south of the Olympic venues. Additional Olympic facilities for Press and Broadcasting are to be housed in structures adjacent to the Boston Convention and Exhibition Center.

Students are to choose and develop only 1 of the following 4 scopes:

- Urban Design and Infrastructure scope of the Olympic venue in Midtown, taking into account connections to existing transit and neighborhoods, as well as scenarios for Post-Game uses.

- Landscape and waterfront design of the Fort Point waterway and Olympic venue in Midtown, with the understanding that the new waterfront must function as green infrastructure, accommodating contemporary thinking about sea level rise and urban waterfronts.

- Architectural scale design of the purpose built Olympic stadium, with the intent that it be dismountable, and/or adaptively reused.

- Architectural scale design of a purpose built facility for a sports venue, such as Track Cycling (currently described as “additional”), or Beach Volleyball (currently described as “temporary”).

Jury

Eric Howeler, FAIA

Jury Chair & Program Author

Principal, Höweler + Yoon Architecture

Chris Reed

Founding Principal

Stoss Landscape Urbanism

Mariana Ibañez

Associate Professor of Architecture

Harvard Graduate School of Design

Nancy Ludwig, FAIA

President

ICON Architecture, Inc.

Mark Hutker, FAIA

Director, Lyceum Fellowship

Principal, Hutker Architects